Africa is the continent with the largest number of countries in the world. Situated almost at the center of the global map, Africa was once a brutal victim of colonization. It is naturally blessed with scenic beauty and vast natural resources. In terms of both area and population, Africa is the second largest continent in the world. However, despite these advantages, it remains the poorest continent globally.

This economic contradiction has drawn the attention of economists and policy experts for decades. Why has poverty persisted across much of Africa despite its immense natural wealth? In this article, we explore this question by examining historical, political, and economic factors based on existing research and analysis.

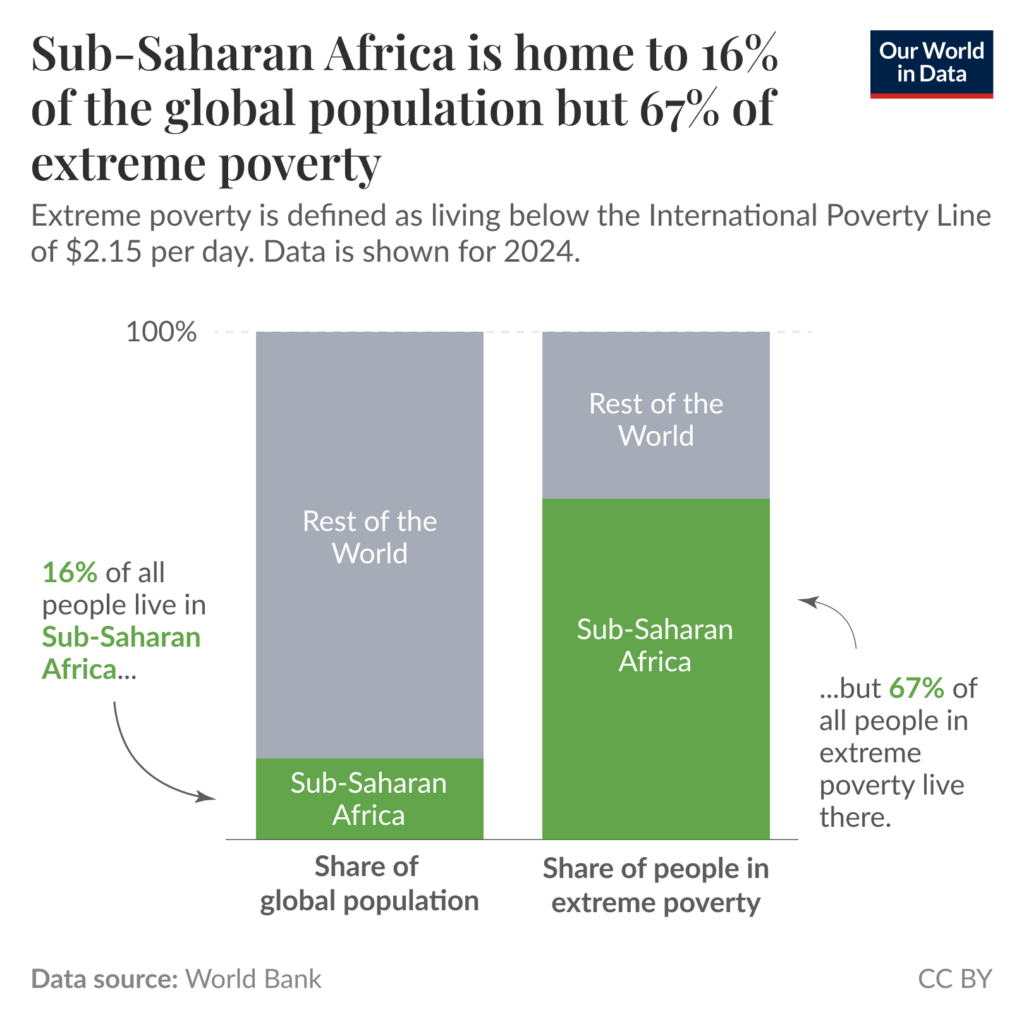

Let us begin with some data to understand the scale of inequality in Africa. Most of the continent consists of Sub-Saharan Africa, which is separated from North Africa by the Sahara Desert. Africa’s total population is approximately 1.5 to 1.6 billion, making it the second most populous continent after Asia. Yet among the world’s 20 poorest countries, 18 are located in Sub-Saharan Africa. According to the United Nations, 46 economies worldwide are classified as least developed, and 33 of them are in Africa.

Although Sub-Saharan Africa is home to only 16 percent of the world’s population, nearly 67 percent of the world’s people living in extreme poverty reside there. The scale of poverty becomes unmistakably clear through these figures.

Africa’s resource endowment, however, is equally striking. From fertile agricultural landscapes to vast mineral reserves beneath the surface, the continent’s natural wealth is extensive and diverse. According to the United Nations, Africa holds approximately 40 percent of the world’s gold reserves and around 30 percent of global mineral reserves. In addition, the continent possesses significant deposits of rare minerals essential for modern technology.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) alone accounts for roughly 70 percent of global coltan reserves, one-third of global cobalt, 10 percent of global copper, and 30 percent of diamond reserves. Despite this extraordinary wealth, the DRC remains among the poorest countries in the world. According to World Bank data, its poverty rate stands at approximately 85 percent. Similar contradictions are visible across much of the continent.

Let us now turn to the historical context. Africa’s modern history is deeply intertwined with colonization. With the exception of Liberia and Ethiopia—though Ethiopia experienced a brief Italian occupation during World War II—nearly all African countries were colonized by European powers. The effects of colonization continue to shape African societies, economies, governments, and institutions.

Colonial administrations systematically extracted resources, often through coercion, to fuel industrial growth in Europe. Much of Europe’s historical wealth accumulation was driven by resources taken from colonies across the world, including Africa. Prior to colonization, African societies functioned within the norms of their historical era. Notably, Mansa Musa of Mali is often regarded as the wealthiest individual in recorded human history.

The arrival of European powers disrupted these trajectories. The transatlantic slave trade remains one of the most tragic episodes in human history, with an estimated 10 to 15 million Africans forcibly transported—primarily to the Americas—and subjected to enslavement.

Most scholars agree that colonial legacy is a major factor behind Africa’s persistent poverty. However, it does not explain everything. Nearly seventy years have passed since the end of formal colonization in most African countries, yet broad economic transformation has remained limited. With a few exceptions, sustained development has proven elusive.

A widely cited explanation lies in post-colonial political and social instability. Colonial borders and governance systems, designed for control rather than cohesion, left many African states with fragile institutions. State capacity remains limited in many rural areas, and economic modernization has progressed slowly.

Although formal colonial rule ended, external intervention continued. Foreign powers frequently supported authoritarian leaders or undermined popular governments to protect strategic and economic interests. Political instability fostered mistrust, internal conflict, and prolonged periods of war and famine. While international aid has flowed into the continent, long-term productive investment has remained limited, and aid distribution has at times intensified internal tensions.

Today, more than 50 active armed conflicts persist across Africa. Even United Nations peacekeepers have come under attack; recently, six Bangladeshi peacekeepers lost their lives in Sudan. Prolonged conflict makes sustained development nearly impossible. In contrast, many Asian countries that gained independence during the same period—such as India, Malaysia, and Indonesia—experienced stronger economic growth, aided by relative political stability.

Corruption and weak governance further compound these challenges. Estimates suggest that approximately $10 billion drains from African economies annually due to corruption. Other reports place losses from illicit financial flows, corruption, and theft at over $100 billion per year. These losses undermine investment in infrastructure, healthcare, and education, while discouraging foreign and domestic investment. Corruption also empowers armed groups and criminal networks, deepening instability.

Weak institutions, persistent political instability, and the concentration of power in unaccountable leadership structures have played a significant role in undermining peace and the rule of law across many African states.

Conclusion: Beyond Resources, Toward Responsibility

Africa’s poverty in the midst of immense natural wealth is not the result of a single failure, nor can it be reduced to simplistic explanations. It is the outcome of historical extraction, fragile institutions, prolonged conflict, and unequal integration into the global economy—forces that have shaped how resources are controlled and who benefits from them.

Natural resources do not guarantee prosperity. When embedded in systems that reward secrecy over transparency and power over public welfare, resource wealth often deepens inequality instead of alleviating it. These dynamics are reinforced not only within national borders, but also by global markets that depend on African resources while exporting environmental, social, and economic costs back to producing regions.

Responsibility, therefore, is shared. Sustainable development requires accountable governance within African states, but it also demands reform of global financial systems, fairer trade relationships, and an end to extractive practices that concentrate wealth abroad. Africa’s future will not be determined by its resources alone, but by the structures—local and global—that shape how those resources are governed.

The central question is no longer why Africa is poor despite being rich, but whether the global systems that profit from its wealth are willing to change. Real progress begins when extraction gives way to investment, and when prosperity is measured not by what is taken, but by what is built and sustained.

Supporting References:

Share this article